Rationalizing Death Rituals: In many societies, there are beliefs and customs associated with death. One common practice is that when a person dies, their family members are expected to stay home for several days and avoid social gatherings—such as visiting temples, attending weddings, or participating in ceremonies. But where do these traditions come from, and are they still relevant today? Let’s explore the origins of these customs and consider their rationality.

Many of these beliefs date back to medieval times when political, caste, religious, and social norms were shaping societies. During that era, people often did not understand the cause of death—whether it was due to a contagious disease or something non-communicable. As a precaution, they introduced guidelines like the 14-day or 21-day isolation periods, which varied by region and evolved over time. Even though our understanding of disease has vastly improved, these customs are still widely observed.

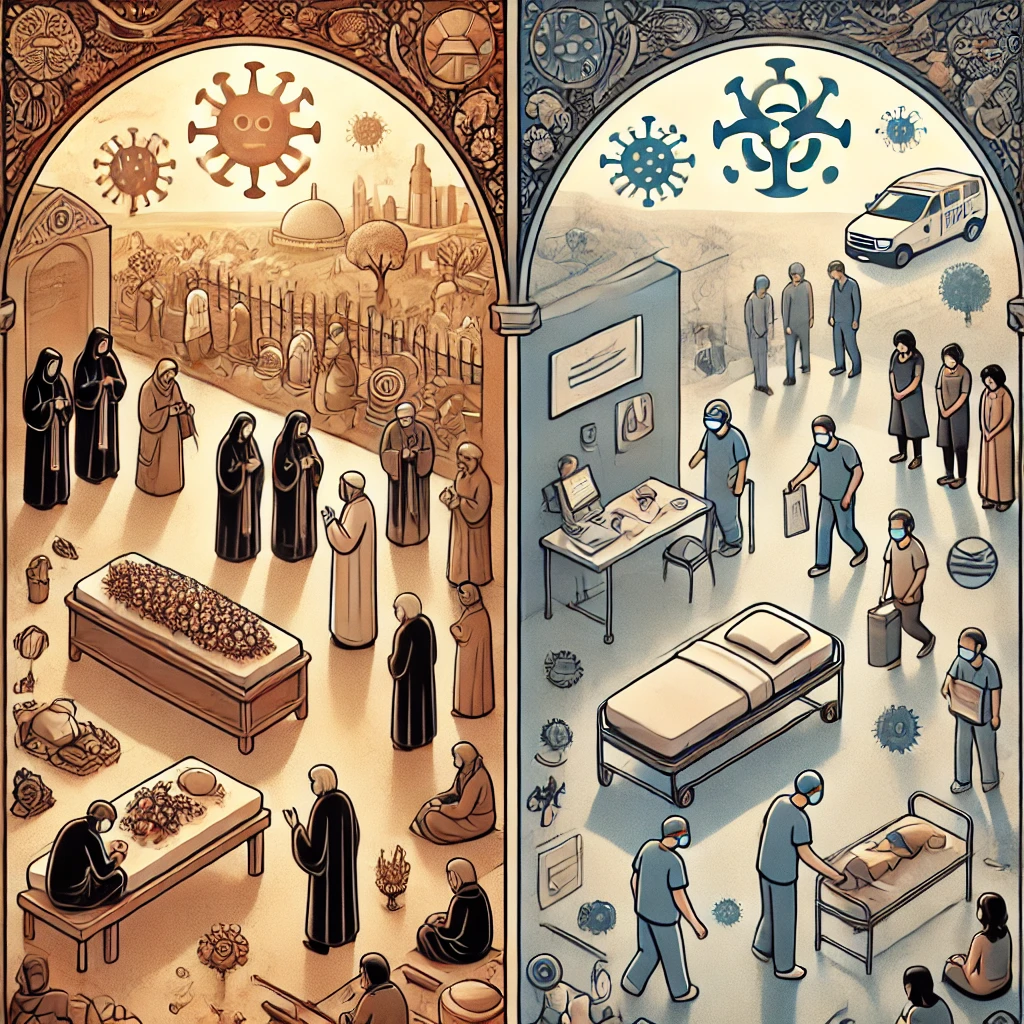

To relate this to recent history, consider the COVID-19 pandemic. When a contagious disease begins to spread, it usually takes 2 to 3 weeks for the infected individual to exhibit symptoms, for their body to produce antibodies, and for the disease to be fought off or cured. If a person died from a transmissible illness, it’s logical that their family members—who may have been exposed—should avoid social gatherings to prevent further spread of infection.

However, in India, roughly 75% to 80% of deaths are due to non-communicable diseases. Despite this, many people still adhere to the traditional 14-day mourning period. This raises an important question: if the reason behind a ritual isn’t clearly communicated, it risks becoming outdated and may even have negative consequences. In the case of a death caused by a contagious disease, unrestricted social interaction can lead to a wider outbreak. Conversely, imposing isolation on families affected by non-communicable diseases can lead to unnecessary social and emotional hardship.

It’s time we bring logic back into rituals, making them reasonable and relevant to the present day.